THE "FAMOUS Old Dark Blues" last week went some way towards removing an infamous old dark stain on their otherwise proud history with Aboriginal players.

On the sunny Monday morning of May 16, Carlton formally acknowledged – almost 90 years after the fact – that a Blues regime had racially vilified a young Doug Nicholls.

Mavis Thorp Clark's 1965 biography Pastor Doug, written in collaboration with Nicholls, reveals that in the pre-season of 1927 the then 20-year-old speedster from southern New South Wales went to Princes Park because a Blues scout had told him, "If you come to town, try us at Carlton – we'll give you a go."

However, Nicholls missed out on the final playing list, told he was too small. (At just 157cm, he remains the equal-second shortest League player ever.) But he suspected other factors were at play.

Pastor Doug exposes the ugly truth: "He was not really surprised. The weeks had not been happy. His teammates were not eager to play with an Aborigine. No one would willingly give him a rubdown. There were complaints that, because of his colour, he smelt. Doug was bitter about that, though he did not say anything."

It's important to note that Nicholls was known to underplay the racism he was subjected to.

Nicholls' daughter Pam Pedersen told the AFL Record: "Dad hardly spoke about that horrible episode at Carlton. He must have been too sad.

Below: AFL chief Gillon McLachlan and Pam Pedersen. Picture: AFL Media

But he always carried it with him."

Pedersen, known as 'Aunty Pam', is a Yorta Yorta elder and respected community leader in her own right.

She was last year invited to join Carlton's Reconciliation Action Plan advisory board ("I only agreed because of what happened to Dad," she insisted) and was pleasantly surprised when told the club planned to officially reconcile with her family.

"Some family members may still be bitter, but I'm not – I respect the club for trying to make amends," Aunty Pam said.

So it was that the Blues invited the Nicholls clan to an intimate 'Galnyan Yakurrumdja' – which Aunty Pam translated as 'respectful acknowledgement' – attended by club management, staff, the football department and players, including Aunty Pam's nephew Andrew Walker.

Blues CEO Steven Trigg took to the lectern and expressed disappointment that it had taken so long to clear the air on the issue, lamenting "the pain, the hurt, the grief" it had caused Nicholls, his family and his people.

Trigg, who hailed Nicholls as one of Australia's greatest leaders and a reconciliation pioneer, condemned as "completely unacceptable" the conduct of certain unnamed Carlton officials and players for not affording Nicholls "the opportunity to flourish as his talent and his character should ordinarily dictate".

"He was excluded … due to his Aboriginality," Trigg said. "It's worth thinking for a moment about how those actions must have made him feel."

In response, Aunty Pam gracefully accepted the apology and declared that justice had finally been done.

Her father had been made to feel "inferior" by "hateful words", she said.

She described it as "a painful story that has crossed the generations" and had been "burned into the Nicholls family psyche"; a story that has remained "frozen in time" and has "just sat there festering" like an open wound.

As for how her father would have felt about Carlton's apology, Aunty Pam told the Blues: "He would be charitable, he would be forgiving, he would have let the bitterness go … he would have thanked you."

The Blues would soon regret their disdainful dismissal of Nicholls and made at least two bids for him to return to Princes Park, both of which proved unsuccessful for obvious reasons.

Aunty Pam reminded the Blues: "You missed out big time … (on) having an amazing sportsman in your midst … and a remarkable person … Dad (became) an Australian icon."

Aunty Pam concluded her speech with: "Let us now walk together," and then everyone walked together on to the ground and formed a circle for a smoking/cleansing ceremony.

The Nicholls family presented the Blues with a coolamon and a shield and in return received a Carlton guernsey featuring Sir Doug's tribal totem of an emu and a turtle.

Such was just the latest recognition of a man whose legacy continues to shape lives.

Nicholls, the man now honoured by the AFL in its rebadged Sir Doug Nicholls Indigenous Round, is a unique figure in Australian history.

His chances of success had been so slim that, in football parlance, he started 10 goals down against a gale-force breeze.

Born on December 9, 1906, Nicholls grew up on Cummeragunja Aboriginal mission in southern New South Wales, where he learned to play football barefoot but was basically illiterate.

As the Carlton affair so graphically highlighted, these were less-enlightened times. Officially, Aborigines weren't deemed Australian citizens.

This was most devastatingly reinforced for Nicholls at the age of eight when he watched helplessly as police forcibly removed his teenage sister Hilda.

And when he "hitched a ride on a loaded cattle truck" to Melbourne, Nicholls had little money, no job, no friends, no concept of city life and, potentially, few prospects.

Initially he slept in fruit boxes at Victoria Market where he scrounged a job.

So it's simply remarkable that, as Aunty Pam and her niece Ngarra Murray (Sir Doug's great-granddaughter) like to say, "a boy from 'Cummera' made it all the way to Buckingham Palace".

As Ngarra (the sister of ex-Bomber Nathan Lovett-Murray) so succinctly puts it, Nicholls was "a man of many firsts" for his people, including being the first Aborigine to be knighted (for "distinguished services to the advancement of the Aboriginal people") and the first to hold a vice-regal office (as Governor of South Australia).

Sir Doug Nicholls with the Queen and Prince Philip

Nicholls was also named the Victorian Father of the Year, was crowned King of Moomba, dined with Queen Elizabeth II, had an audience with Pope Paul VI, had a Canberra suburb named after him and became a religious leader (affectionately known as 'Pastor Doug'), through which he formed friendships with visiting black American entertainers such as Louis Armstrong and Harry Belafonte, while remaining a champion of the downtrodden.

Nicholls' descendants believe that even with the best opportunities of today, it would be difficult to emulate his achievements.

So has any other Australian achieved so much after coming from so little?

"Probably not," renowned historian Professor Stuart Macintyre said, while pointing out other candidates, including fellow Aboriginal sportsman/activist Charles Perkins and certain convicts.

In 2008, Melbourne writer Michael Winkler argued that Nicholls was the greatest man to play League football and suggested he might well be our greatest Australian.

It's little wonder then that Jason Tamiru, a grandson of Nicholls, declared in Peter Dickson's superb documentary The Story of Legend: Sir Doug Nicholls that his grandfather's epic tale is "one of the greatest stories, not only just of Australia …(but) of the world".

The catalyst for Nicholls' ascension to iconic status was his football stardom, when he was the only Aboriginal League player of his era.

Lightning-quick, spring-heeled and brave, the "pocket Hercules" became one of the VFA's most spectacular and popular players.

"I was quick on my feet and quick of eye," he once explained. "I got it from my ancestors – they needed it to get out of trouble."

In five seasons at Northcote, Nicholls won two best and fairests, finished third in the league count, starred in three consecutive grand finals, including the club's first premiership in 1929, and twice represented the VFA, on one occasion performing strongly against the VFL.

"To me, the roar of the crowd is music," he told The Sporting Globe in 1935.

Work was scarce during the Depression, so Nicholls spent his off-seasons running professionally (winning the Warracknabeal and

Nyah Gifts) and as part of Jimmy Sharman's travelling boxing troupe, sending money home to Cummeragunja.

Nicholls said boxing, often against much bigger opponents, gave him confidence and self-control "in ticklish situations", which came in handy on the football field.

"Sport was my university … (it) assimilated me into the community," he told The Australian Women's Weekly in 1957.

If not for Sharman, Nicholls might never have played league football.

In early 1932, his suitors included Carlton, Collingwood (which he'd almost joined in the late 1920s) and Fitzroy.

The problem was the 25-year-old had signed a lucrative three-year contract with Sharman and was prepared to honour it.

But the veteran showman mercifully released Nicholls when Fitzroy also agreed to give him the job of curator at Brunswick St.

Despite an early knee injury that required the removal of a cartilage, Nicholls flourished at Fitzroy, just as he felt he would have at Carlton if given the chance.

The wingman made his debut against the Blues at home and enjoyed what must have been a sweet victory.

In a 1933 win over St Kilda, The Sporting Globe credited Nicholls with 30 kicks.

The next year he finished third in the Maroons' best and fairest.

It's instructive that Nicholls was made to feel welcome at Fitzroy.

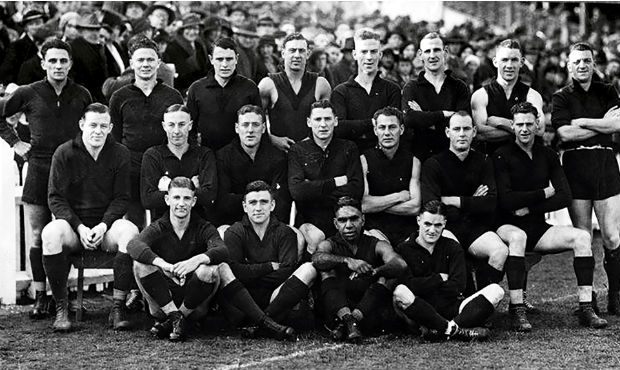

Doug Nicholls with his Fitzroy teammates in 1933

Before his first training session, Nicholls changed in a corner away from his new teammates, so young superstar Haydn Bunton asked him: "What's the idea? Why aren't you with the others?"

"We-e-ell," Nicholls replied, "you know how it is."

Thereafter, Bunton always changed alongside him, cementing a warm friendship.

After Bunton was killed in a car accident in 1955, Pastor Doug officiated at his memorial service, telling the large gathering, "We are here to pay tribute to a man we loved."

The race issue led to a potentially explosive confrontation with another of the game's household names.

Richmond enforcer Jack Dyer crunched Nicholls on the field and delivered a racist barb that had hurt far more.

Sometime later in 1935, the pair became teammates when Nicholls was the first Aborigine to be selected to represent Victoria.

As the Trans Continental train carried the Vics towards Perth, Nicholls stared down the young Tiger giant.

When Dyer asked what the problem was, Nicholls snarled: "I don't like you, Jack Dyer – for what you said."

Those in earshot were shocked – after all, lay-preacher Nicholls had only ever been known as quiet and pleasant.

Dyer immediately apologised and they became friends.

On that trip west, during which Nicholls delivered sermons at churches in Adelaide and Perth, he became more determined than ever to help his people after witnessing the "tragic" condition of some Aboriginal communities.

Nicholls played just 54 League games, but football proved a stepping-stone to greater things. In some ways, his impact on the game and society continues to grow.

Ngarra welcomed another groundbreaking achievement for her great-grandfather, who has become the first person to have an AFL round named after them.

"It's great because now a lot more people will learn and become inspired by his amazing story," Ngarra said.

Aunty Pam added: "It's wonderful. A beautiful acknowledgement of a beautiful person."

What would the great man himself say about the honour?

"He'd be so proud it might bring a tear to his eye," Aunty Pam said.

"But just like Dad did before he became governor (of SA), first he'd ask the family what we thought. He never thought it was just about him."

Aunty Pam emphasised that her father would have struggled to achieve all he did without the unwavering support of his family and friends.

Nicholls' greatest ally was his wife, Lady Gladys, who assisted and advised him.

A statue of this regal couple stands in Melbourne's Parliament Gardens.

The circumstances behind their marriage reveals much about Nicholls.

Lady Gladys' first husband was Howard 'Dowie' Nicholls, Doug's older brother and ex-teammate at both Tongala (in the Kyabram league) and Northcote (for one season).

Howard died after a car crash in 1942, aged 37. Eight months later, Doug, then 36, married his brother's widow and took on their three children as his own. They had three more children.

Grandson Gary Murray (Ngarra's father) said: "He would've seen it as his cultural duty. We look after our people.

"And that was always at the forefront of his mind."

After his death at 81 on June 4, 1988, Nicholls was afforded a State Funeral before being laid to rest alongside Lady Gladys at Cummeragunja cemetery.

A descendant of tribal "kings, queens and headmen", Nicholls believed that everyone should make a contribution to the community, and many members of his family continue to do just that, in a variety of ways.

One of them, grandson Tamiru, a producer of indigenous performing arts, summed up his grandfather's broad influence in Dickson's documentary: "His legacy for me is great integrity, compassion, fair go, mateship, human rights, civil rights, spirituality, identity, culture (and) a place in the earth."

'That caused a great ruckus'

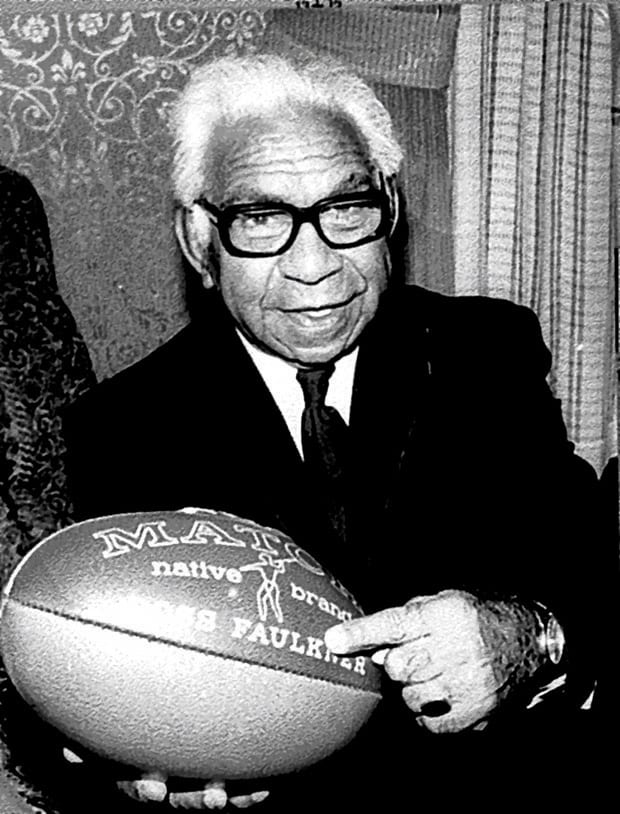

A SIGNIFICANT yet little-known influence on Doug Nicholls' VFL and VFA careers was football manufacturer Ross Faulkner, whose links with the Aboriginal great are detailed here for the first time.

The AFL Record tracked down Faulkner's grandson of the same name – the fourth generation to own and run the family business – who revealed that the Faulkners' deep respect for Aborigines traced back into the mid-1800s when a white ancestor spent a considerable time living with a tribe in north-east Victoria.

The original Ross Faulkner was a committeeman at VFA club Northcote and his inclusive nature proved a refreshing contrast to Carlton's prejudice towards Nicholls in 1927.

"My grandfather had heard how this talented Aboriginal boy had been mistreated at Carlton and he thought that was utterly despicable, so he got Doug to Northcote," the younger Faulkner said.

Five years later when Nicholls again pursued a League career, Faulkner, then a committeeman at Fitzroy, again intervened at a critical juncture.

"My grandfather and his great friend Percy Mitchell (another official) were integral to getting Doug to Fitzroy," the proud grandson said.

Faulkner was so taken with Nicholls that he introduced the 'native brand' logo to his footballs.

"That was out of recognition for his great friendship with Doug and the family connection to Aboriginals," Faulkner said.

"In those days it wasn't a smart business decision to name your brand after an Aboriginal and give them recognition. In some ways it was quite confronting.

"My grandmother told me about a memorable incident at a game between Fitzroy and Melbourne at the MCG.

"My grandfather was in the committee room when a Melbourne committeeman came up to him and passed some very derogatory remarks about Doug and Aboriginals in general.

"My grandfather promptly responded by knocking him out. That caused a great ruckus."

Nicholls and Faulkner shared a lifelong friendship and the younger Faulkner said, "a great understanding of a subject that remains so difficult".

And today the legacy continues, with the Ross Faulkner company involved in programs that encourage young Aborigines to get an education and play sport.

These are edited versions of stories published in this round's edition of the AFL Record, available at all venues.

Sir Doug Nicholls with a Ross Faulkner 'Native Brand' football