HE'S THE little-known inspiration behind one of the most famous AFL Grand Final speeches.

A mischievous plan was in motion as Luke Chambers, one of the AFL's faceless men, flanked Hawthorn football manager Mark Evans on the hallowed turf of the MCG.

They were there, to Geelong's knowledge, to do a ground inspection on Grand Final eve in 2008.

Chambers, an opposition analyst at the Hawks, had loftier motives.

He crossed the 'G and entered its stands, finding a nondescript spot – with only his sunglasses for disguise – to secretly watch the Cats' final closed training session.

Chambers' discovery, relayed to Hawthorn coach Alastair Clarkson, was crucial: all of the Mark Thompson-coached team's gameplay drills went through the corridor.

Fast-forward to Grand Final day and Clarkson, before winning the first of four premierships that sealed his legacy, implored his players to "kill the shark".

The idea behind the combative words, with a Great White Shark projected onto a whiteboard for dramatic effect, was for his Hawks to stifle Geelong's direct ball movement and force it wide.

"Sharks have to move forward … as soon as they stop, they die," Clarkson roared in his pre-match speech, immortalised in the documentary The Essence of the Game.

"(Geelong) will try to come through us like a shark …

"Good luck to them on a big stage like the Grand Final, with lots of pressure, (against) the best defensive-pressure side in the competition."

Chambers ironically later worked as a senior analyst for Thompson at Essendon – a role he filled at Melbourne before that – but never told the dual premiership coach of his deception.

He left the AFL industry for good in the fallout from James Hird's ugly exit as the Bombers' senior coach in 2015, and now works in the banking sector.

Hawthorn celebrates the 2008 premiership win. Picture: AFL Photos

THE LIFE OF AN OPPOSITION ANALYST

Opposition analysts are the too-often-forgotten treasures at AFL clubs largely left to their own devices to work unforgiving hours.

They usually haven't played above grassroots football, but boast sharp footy minds with an ability to break down structures – live and on laptops – identify trends and create solutions.

Neil Craig, Brendon Bolton and Chris Fagan bucked the trend in becoming senior coaches despite not playing AFL, so it is conceivable an opposition analyst could climb to the top, too.

John Wardrop, who worked at Hawthorn and Collingwood and is now at West Coast as its head of game analysis, is considered the "godfather of opposition".

Multiple scouts told AFL.com.au they used to watch 100 games live a year.

The current limited pathway, huge workload, intense pressure and sometimes a lack of appreciation – this came up several times – means few last long-term before leaving.

"In terms of the lifestyle; in a lot of ways it's the hardest job in footy," one opposition analyst said.

"I might fly up to Sydney on the Friday night, fly back and be at Etihad watching a game the next day, then be in the box for us on the Saturday night.

"On Sunday I'd fly to Perth, come back on the red-eye, and Monday morning you have to be ready to go for the next week."

Essendon scout Rob Harding defines the role of an opposition analyst as "a PhD in footy".

"It doesn't teach you about culture, environment, values or relationships – and they're huge – but it is a great grounding in this one area," he said.

Chambers was studying neuroscience at university when he started working at Hawthorn.

"I wrote to the clubs and wanted to get into recruiting initially. A lot of the clubs want kids who are scientific thinkers," Chambers said.

Harding made his start in the AFL industry working full-time in video analysis and statistics at North Melbourne after being an SEN radio producer.

He soon became the Roos' opposition analyst, was at Geelong for its 2011 flag, then followed Brenton Sanderson to Adelaide before joining Essendon last year.

Harding is the Bombers' game intelligence and opposition strategy coach and works in tandem with high-profile coaches John Worsfold and Mark Neeld to develop the club's tactics.

WHEN EVERYTHING CHANGED

THE AFL's decision to begin supplying behind-the-goals vision to clubs about a decade ago was "the biggest game-changer in this role", according to Harding.

He used to attend four live matches a round, but that number reduced to one or two from 2013, although he watches, in some shape or form, all nine or a minimum of eight a week.

It is more resourceful to download and analyse the behind-the-goals vision post-games – it is accessible instantly at clubs' own matches – and pick up on trends, tactics and threats that way.

Champion Data's increasingly in-depth statistical data has also transformed football analysis.

"The game changed a lot when the vision came into it … before that, we were taking photos of stoppages, because the broadcast vision wasn't good enough," Chambers said.

"We were actually taking photos from the stands, so we were smuggling in a long-range camera and literally getting positions behind the goals and taking shots."

Some clubs even parked a staff member behind the goals who would text a colleague in the coaches' box with what they were seeing.

Former West Coast opposition analyst Mark Stone, who was an assistant coach at Sydney and Fremantle and now coaches Glenelg, would diagram rival sides' stoppages on PowerPoint.

"I remember going to a couple of games and seeing guys hold their phones up and take photos, but we never did it," Stone told AFL.com.au.

"(Then Eagles coach) John Worsfold and Tim Gepp were ethically against it, so we didn't do it.

"If we couldn't watch it with our own eyes and break it down off tape, and then explain it to the coaches and the players, then we weren't good enough."

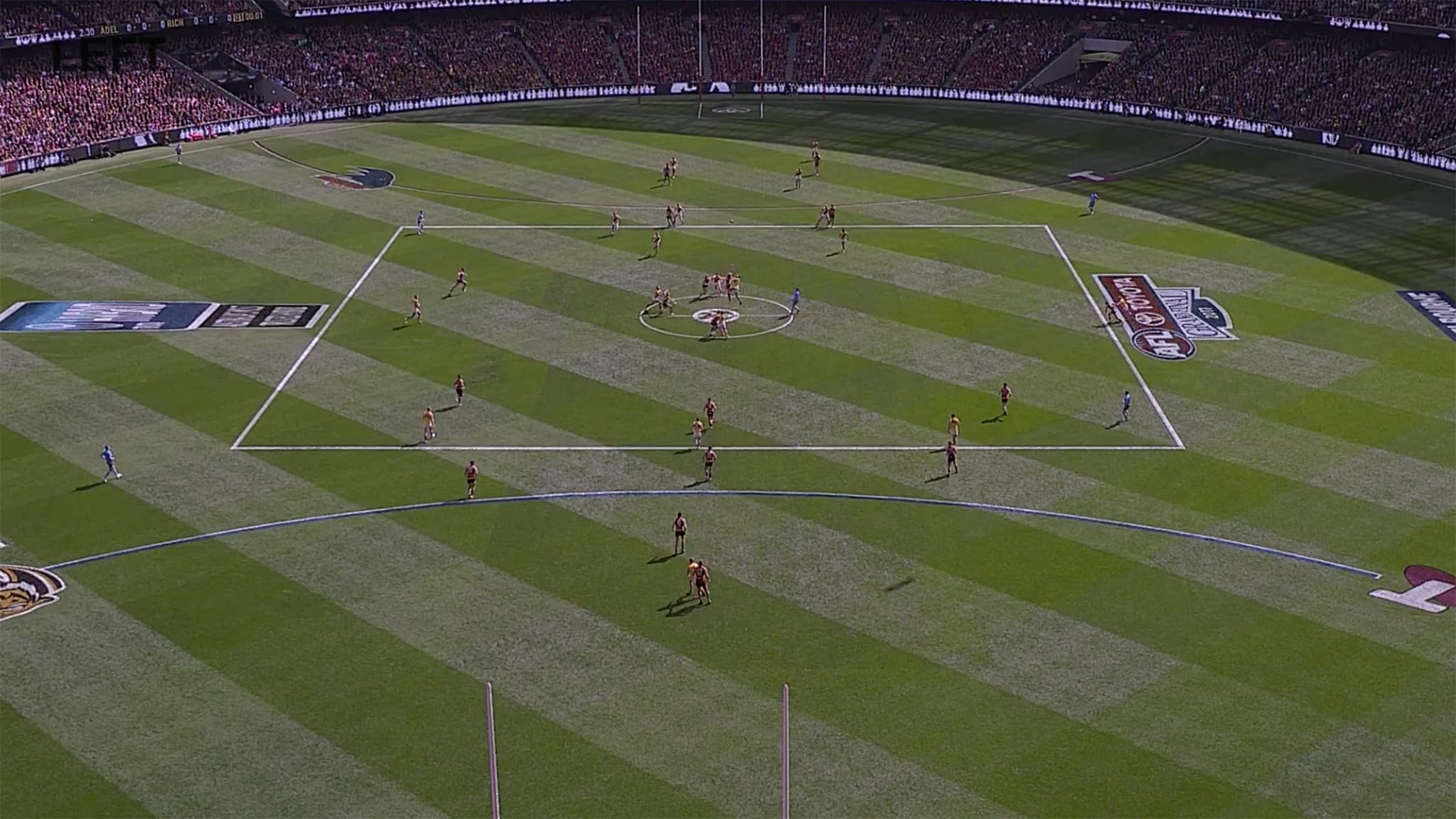

Behind the goals footage from the 2017 Grand Final.

SUBTERFUGE: FAKE FANS AND SLEEPING BAGS

You may have unwittingly met some opposition analysts if you're a rusted-on fan who attends training sessions.

An opposition analyst told AFL.com.au he would spend "thousands of dollars on footy gear" to blend in as a supporter.

Another, Damien Zanic, who studied the opposition for Leigh Matthews' legendary Brisbane sides between 2001 and 2004, occasionally brought his son to training as part of the ruse.

He would quiz fans, acting as one of them, about certain players and the team in general: Who is injured? How are they going? What position is he training in?

Sometimes Zanic's young son would even do the questioning.

"I'd go to opposition training and no-one would know who I was," Zanic said.

"There was one day – I think I was at the Western Bulldogs – and I had my son with me and we were having kick to kick on the ground.

"I'd take the camera out and look like I was taking photos of him, but instead of doing that I'd be taking photos of the stoppages in the background."

St Kilda's old football manager Greg Hutchison marched up and down the Saints' Seaford base in his day looking for spies and booting them out, like many others did at other clubs.

"You'd be hiding in the trees and see someone else doing the same thing you're doing and it's pretty funny at times," Harding said with a grin.

But that doesn't come close to other extreme measures taken.

Like Chambers' 2008 Grand Final week story highlighted, opposition analysts up the ante when the stakes are at their greatest.

One of them slept overnight in an Ikon Park coaches' box to spy on Carlton training before a final.

"I'd go in the night before and take my sleeping bag and sleep in there, then watch the whole training session and you'd know basically everything they were doing," he said.

"There's one with a padlock on it and the lock wasn't locked, but I made it look like it was shut, so that if anyone walked past they just presumed it was a locked coaches' box.

"I'd wait hours until they finished training and then duck out."

Another story, again at Seaford, involved an opposition analyst arriving at the break of dawn to ensure he gained his prime car spot, which offered a great view with the sun shade down.

The problem? The Saints didn't emerge for training until noon and it was a 40-degree day.

"What you're doing is trying to find that one percent edge, from a number of different spaces, and hope it adds up to something."

It might even be the difference between winning a premiership or not.