HUGHIE James gave everything for both Richmond Football Club and his country.

Two premierships, club champion status and a stint as captain are ample proof of his Tiger devotion, while a Military Cross and Bar earned for acts of bravery 100 years ago stand testament to James' fierce patriotism.

The irresistibly likeable, ever-smiling Tiger of old died 50 years ago – two days before Anzac Day in 1967 – but his family continues to give.

It's the morning after Richmond thrashed old enemy Carlton in the season-opener at the MCG and we're just a few hundred metres away in the victor's lair at Punt Rd Oval.

Margaret-Anne Faulds (one of James' six grandchildren) and her mother Marion James (James' widowed daughter-in-law who was married to his only son Laurie) have made a special trip to the Tigers' museum to donate a vase bearing the inscription: TO HUGHIE JAMES, IN APPRECIATION OF HIS YEOMAN SERVICE TO "THE TIGERS" ESPECIALLY SEASON 1923. FROM E.H. KING, VICE PRES.

Both women have travelled a long way to be here on this warm March day.

Family pride: Grandaughter Margaret-Anne Faulds and daughter-in-law Marion James

They hail from Wellington, New Zealand, where James spent the last 35 years of his life, and where Marion James still resides. Her daughter moved across the ditch to Sydney some years back after marrying an Aussie.

Neither are AFL fans, so they are pleasantly surprised by the reverence in which James is still held at Tigerland.

They describe him as kind, charismatic and a great people person – qualities that partly explain why The Argus' 'Old Boy' in 1934 hailed James as "one of the most popular men who ever played".

"The family is immensely proud of Papa," Faulds said. "But he was so understated – he never lived off his past successes. I don't think he even saw them as exceptional. He always lived for the now and the future."

Sharing their pride is Jack James, who was born a month before his uncle Hughie's last game with Richmond in 1923.

From a retirement village in Keilor, the 93-year-old said: "I was rapt that he was my uncle – for everything he achieved, but mainly because he was just a very good man."

Born on May 4, 1890, John Hugh 'Hughie' James was the eldest of four brothers – the others being Arthur (Jack's father), Laurie and Keith – born in the Gippsland region before the family relocated to the Essendon district.

The siblings formed their own building business, Jack James revealed, in which all-rounder Hughie looked after the paperwork, Arthur was the chief bricklayer and Laurie was the carpenter.

Hughie was the only James boy to play League football, but that dream appeared in tatters when, at 17, he was discarded by his local VFA club Essendon Town. Not surprisingly, James later relished every victory against Essendon's VFL side.

After a stint with VFA rival Preston, James quickly established himself with fledgling VFL club Richmond, where he became one of the great ruckmen of the League's early years.

Though a poor kick – a source of much mirth at Tigerland – James compensated with superb high marking, deft tapwork, toughness and composure.

Richmond struggled pre-war, but The Sporting Globe's renowned scribe Hec de Lacy later noted that James "stood out for the quiet good-fellowship he engendered", adding that "it was his infectious confidence that carried the Tigers" through their infancy.

Praised as the League's fairest and most popular player because of his "many fine and manly qualities", James showed rare sportsmanship in a close game against Essendon.

After Richmond scored a behind, the ball returned from the crowd with a puncture. The Dons full-back kicked it towards the field umpire hoping for a replacement, only for a Tiger to pounce for a crucial goal.

An indignant James demanded, unsuccessfully, that the goal be removed from his team's score.

"Nobody is keener to beat Essendon than I am," he told teammates, "but I won't have a win as the result of an honest mistake like that."

A mistake could have denied James his chance to serve his country.

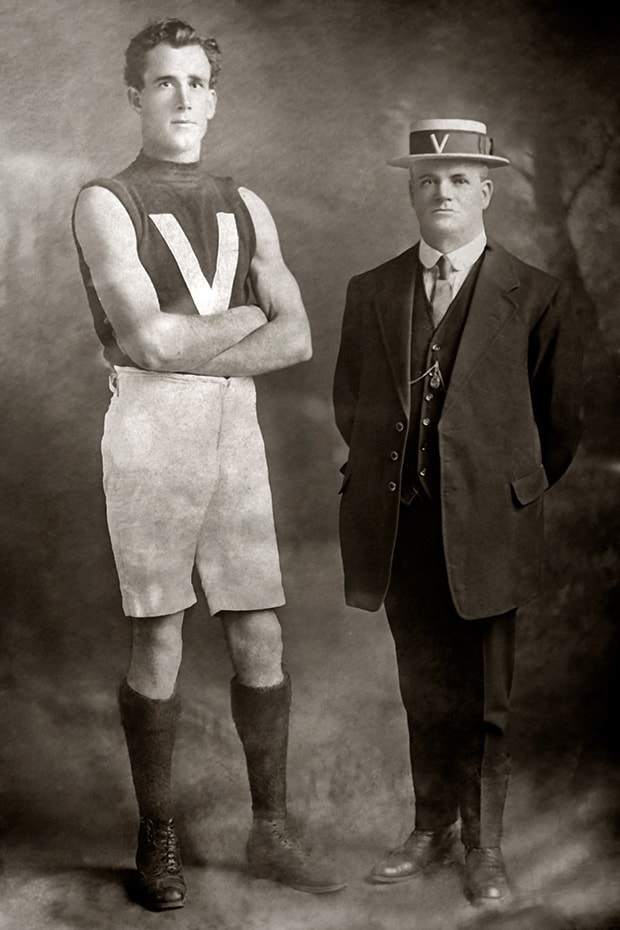

In his prime: James established himself as one of the great ruckmen of the VFL's early years.

When he went to enlist in Melbourne in January 1916, he was initially rejected for failing an eyesight test. Suspecting a mix-up, James sat another test on the other side of the street and was accepted.

"I thought it was up to me to do my share," James told The Argus. "You see, I'm young and in good condition. And who knows? I might be on the ball again in a season or two."

James' enlistment papers note that both of his knees bore scars, which would soon be joined by battle scars.

Then 25, he left behind his wife Ethel and baby daughter Sylvia.

Two of his brothers – Arthur, 22, and Laurie, 20 – had already seen action overseas. (Keith had been too young to enlist.)

Continuing a life pattern of making an impression wherever he went, within weeks Private Hughie James was promoted to the rank of lieutenant.

Over a few drinks with his army pals while training in England, James also came up with the brilliant idea of staging an exhibition football match in London, which came to fruition in October 1916.

The famous event – in which James starred in a victory for the Third Division against the Training Units – helped boost morale among Aussie troops before being sent to the Western Front.

Duty bound: Hughie James with wife Ethel and daughter Sylvia: Picture: Private collection with assistance from the West Wyalong Advocate

The next month James left for France and he'd recall that on January 4, 1917, he'd been "right near" his Third Division football captain Bruce Sloss – the South Melbourne star – when Sloss "got it" from the Germans.

A week later, folks back home thought James had also "got it" when a rumour circulated that he'd been killed.

The rumour, which provoked "expressions of regret" around Melbourne, became so strong that Hughie's father John James and cousin Charles Moore rushed to the Base Records Office in St Kilda Rd for clarification.

They were relieved to be informed there had been no word of Hughie's demise. Just to make sure, a cable was sent to the London headquarters, which replied: "James well at latest."

The next week the Richmond Guardian reported James was "very much alive, thank you", denouncing the "fool" who'd started the "senseless" scuttlebutt.

James was, however, lucky to escape the war with his life, despite proving as cool in battle as he was on the football field.

A valued member of the 3rd Pioneer battalion – a construction unit largely engaged in digging trenches, building bridges and repairing roads – James was, according to a young 'Richmondite' in a letter home, "just as popular here as he was in Richmond".

That popularity was further enhanced when James won a Military Cross for his efforts near the Belgian village of Messines on June 7 and 8, 1917.

He was officially honoured "for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in reconnoitering and repairing a road and constructing a bridge over a river under heavy shell fire. His gallantry under the most trying circumstances was a fine example, and inspired his men with the greatest confidence."

When James' honour was later announced at Richmond's annual general meeting, an old member declared: "I knew he'd do it!"

Meanwhile, Melbourne newspaper The Winner added: "All who know him will realise that he has fully earned it, and trust that still more distinctions will come his way."

They were prophetic words.

But first, James suffered three gunshot wounds on two separate dates just six months apart.

At Passchendaele, Belgium, in October 1917, he received a minor wound to his right arm, but remained on duty and didn't seek medical treatment until the next day.

A month later, his wife received a letter that started ominously – "Dear Madam, I regret to advise you …" – before revealing her husband had been "wounded slightly".

The next time – on the killing fields of the Somme, France, in April 1918 – James copped "mild" gunshot wounds to his upper right arm and lower back, requiring a stint in a London hospital.

Undeterred, just four months later James displayed remarkable bravery to be rewarded with a Bar to his Military Cross. The distinctions were earned just 14 months apart and made him the most decorated League footballer of World War I.

In the early hours of August 22, 1918, James had led an attack near the French town of Bray "with great gallantry and skill" against a strongly held German line.

His platoon suffered many casualties but James, despite being exposed to constant fire, continually walked up and down the line directing and encouraging his men until they were dug in.

The Third Division commander reported that "it was only (James') courage, cheerful disposition and total disregard of danger" that ensured the operation's success.

After driving his men to their objective, James then oversaw the capture of 30 German troops.

He proved "an inspiration to all ranks" and was "worthy of every recognition, especially as this is the first time that he or his men had been in a direct attack on any position".

James' brothers weren't so fortunate – Arthur (Jack James' father) was gassed and died from related health issues at just 45 in 1939, while Laurie suffered a worse fate.

Affectionately known as 'Lol', he was just 22 when slain at Proyart, France, on August 26, 1918 – just four days after Hughie had earned the Bar to his MC.

On the one-year anniversary of Laurie's death, big brother Hughie placed a verse in The Argus that fondly recalled a man who was "always happy and cheerful, with a heart that knew no fear".

As a more lasting tribute, Hughie James later named his only son Laurie.

"(Hughie) never spoke about the war," Marion James said. "None of them did. And we weren't about to ask."

Just eight days after being discharged from the army, Lieutenant Hughie James, MC and Bar, resumed his League career with Richmond in round 12, 1919.

Astonishingly, given his age (29) and all that he'd endured, the battle-scarred hero became an even better footballer post-war.

James hadn't made a finals appearance before the war, but on return he was one of the Tigers' best performers in three successive Grand Finals, including their first flags in 1920-21. He was named club champion in the latter season.

James' other monumental contribution to Richmond had been to recruit his army mate Dan Minogue, the former Collingwood captain who led the Tigers to those early triumphs.

Minogue later described James as "a sportsman and a gentleman, if ever there was one".

Following James' retirement at 33 in 1923 after 188 games, he had brief stints as a Tigers committeeman and a selector.

His life took another fascinating turn in 1932 when the owner of a waterproof clothing business, for whom James had done some building works, asked him to run the firm's new factory in Wellington.

James knew nothing about the industry, but he embraced the challenge, proving such a success that he bought a distinctive left-hand-drive Cadillac.

After initially relocating to the New Zealand capital alone, James was joined a year or so later by his wife and three children.

"His three children adored him – he was a great entertainer and a great talker," Faulds said.

Sport remained a constant, with James playing cricket, tennis, golf and, in his latter years, bowls.

He'd also watch his son Laurie play rugby union before rushing home to listen to VFL games on the radio.

Soon after moving to New Zealand, James mailed his Richmond life membership card to his young nephew Jack, a keen Tigers fan.

"I used that card for the next 30-odd years!" Jack James recalled.

James did his bit for Anzac relations as a long-serving president of the Wellington Returned and Services' Association. He also did much charity work for blind ex-servicemen.

A lifelong smoker, James died from lung cancer just short of his 77th birthday.

Faulds, who was just five at the time, reflected: "I worked in the area where Papa had lived and when people realised my surname was James, they'd ask, 'Are you any relation of Hughie James?'

"He was such a big character and he was so well known and so well liked."