Bill Ruthven and Cameron Baird showed courage under fire – literally – almost 100 years apart. They share a common bond as recipients of Australia's highest military honour.

THE GREATEST honour for an Australian soldier is to be awarded the Victoria Cross "for valour".

Of the 100 Aussies who have won VCs, League football claims links to two of them – long-time Collingwood official Bill Ruthven and one-time draft hopeful Cameron Baird, whose father Doug played for Carlton.

They earned their VCs 95 years apart and were different physical specimens (Baird was a man-mountain, while Ruthven was a small man), but both were one-man fighting machines who showed superhuman courage against overwhelming odds.

And, though popular and upbeat personalities, they were also modest men who deflected

the spotlight.

Michael Madden’s new book The Victoria Cross: Australia Remembers (all proceeds of which will be donated to the Totally and Permanently Incapacitated Ex-Servicemen and Women’s Association of Victoria) features chapters on both men, and it inspired the AFL Record to delve deeper into their remarkable lives.

BILL RUTHVEN: Courage under fire

Time was always of the essence for Bill Ruthven.

For many years ‘Rusty’ Ruthven was Collingwood’s timekeeper and as a younger man he’d displayed immaculate timing – along with extraordinary bravery, initiative and skill – in performing a series of heroic deeds that led to victory in a crucial battle and earned him a Victoria Cross.

Ruthven was revered, and he has been honoured with a secondary school, a train station and a sporting oval in his name, but he remained unassuming and self-effacing.

This admirable trait might have had its roots in his humble, working-class upbringing.

Born on May 19, 1893, Ruthven grew up near the Magpie headquarters at Victoria Park. He came from a line of Collingwood carpenters and followed them into the timber industry, becoming a mechanical engineer.

It’s unclear whether Ruthven played football himself, but the national game – and the local League club – was always a family passion.

In fact, Ruthven later took his promising nephew Allan ‘Baron’ Ruthven to Collingwood, but the Magpies rejected the pint-sized youngster, who would become a Fitzroy legend.

The Baron’s much-loved Uncle Bill was also a pocket dynamo.

On April 16, 1915 – just nine days before the slaughter of Aussie Diggers at Gallipoli – 21-year-old Ruthven enlisted as a private in the 22nd Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force.

Standing only 168cm, he just scraped in for the minimum height requirement – a fortunate development given his subsequent heroics.

Ruthven served in the final stages of the failed Gallipoli campaign before being sent to the Western Front in France in March 1916.

The next month, during fighting near Fleurbaix, he suffered a gunshot wound to his left leg.

However, by January 1917, Ruthven had been promoted to sergeant.

Around this time, Ruthven’s parents wrote to him and expressed their wish for him to come home.

Their son’s prophetic reply was that he “would not return without a Victoria Cross”.

In September 1917, Ruthven completed a bayonetting course in England and achieved the highest marks in a school of 800. Just eight months later, he put these skills into deadly action.

Ruthven was a leading member of the 22nd Battalion’s D Company, which he later revealed boasted a number of “hard heads”, or rough diamonds, which was perhaps fortunate given they found themselves in many dire situations.

“We never could keep an officer. We had about 11 killed in 12 months,” Ruthven told The Argus in 1940.

“Most of the time I had charge of the company.

“We always went into (an operation) with an officer. He might have lasted a week or a fortnight – and then a bloke had to carry on!”

And carry on he did – with astonishing results.

On May 19, 1918, the 22nd Battalion was set a monumental task. They were to take the higher ground near the French village of Ville-sur-Ancre and capture two sunken roads called “The Big Caterpillar” and “The Little Caterpillar”, which were heavily guarded by the Germans.

The 22nd Battalion had never attempted such an offensive, over such a large area and with

so few men.

They launched the surprise attack at 2am.

In frantic hand-to-hand combat in The Big Caterpillar, there were many Aussie casualties including D Company’s sergeant-major, who was severely wounded. Ruthven immediately assumed control.

About 30m away, a German machine gun was wreaking havoc so Ruthven, “without hesitation”, threw a hand grenade towards the gunner, rushed the post, bayoneted a German and captured the machine-gun.

More Germans rushed out of a shelter and were also decisively dealt with.

“Those I did not kill I sent back as prisoners,” Ruthven said when he wrote to his parents.

While reorganising his men, Ruthven noticed enemy movement about 100m away and, armed with only a revolver, he struck out alone and stormed the German dugout, shooting its two occupants.

Incredibly, he then captured the remaining garrison of 32 German soldiers, none of whom were game enough to try to overpower the determined Aussie before his fellow Diggers arrived.

For the rest of the mission, Ruthven continually moved among his men to provide supervision and encouragement, while under fire.

Ruthven noted: “Of the 120 men (involved), only 43 came back, so you can see what the stunt was like.”

Ruthven’s VC citation praised him for showing “the most magnificent courage and determination, inspiring everyone by his fine fighting spirit, his remarkable courage, and his dashing action”.

The next day, on the eve of Ruthven’s 25th birthday, British general Sir William Birdwood personally visited the 22nd Battalion to pay tribute to them and their hero Ruthven.

In a later letter to Ruthven, Birdwood also offered his “heartiest congratulations” and “sincere thanks” for Ruthven’s “splendid work”.

Ruthven informed his parents: “I suppose you will be proud of me soon, for there is some talk of my getting a ribbon, some say the Distinguished Conduct Medal, others the Military Medal.”

He clearly underestimated his efforts.

In July 1918 – a month after being wounded again in France – legendary Australian general Sir John Monash presented Ruthven with a Victoria Cross.

Ruthven was also ordered to attend an awards ceremony at Buckingham Palace but, he recalled, “I liked France better, and I slipped the boat.”

He finally reached London the next month and was formally decorated by King George V.

Ruthven had wanted to remain in action until the war ended, so he was gutted when command forced him home with other VC winners to help with recruitment in October 1918.

He and a few other distinguished soldiers were afforded a special homecoming in front of a big crowd at Victoria Park.

Six months later, thieves broke into Ruthven’s house and stole a number of items, including his VC.

Arrests were made and the VC was recovered with an accompanying note for Ruthven: “Dear Sir – Sorry I took your VC from you … if I had known you were a returned soldier I would never have entered your place.”

Just before Christmas in 1919, Ruthven married his sweetheart Irene White, to whom he’d been engaged before the war. (Three of Irene’s uncles were killed in World War I.) They had two children.

Ruthven, who battled war-related spinal issues for the rest of his life, enlisted in World War II at 48 and served at garrisons and camps around Victoria, finishing as a major.

Ruthven also served his community – as mayor of Collingwood, as a long-time Victorian Labor parliamentarian and as trustee of the Shrine of Remembrance.

All the while he served the Pies as timekeeper from 1939 until his death at 76 in January 1970.

Ruthven’s nephew Graeme Cock told author Madden: “He loved the footy and he loved his Magpies.”

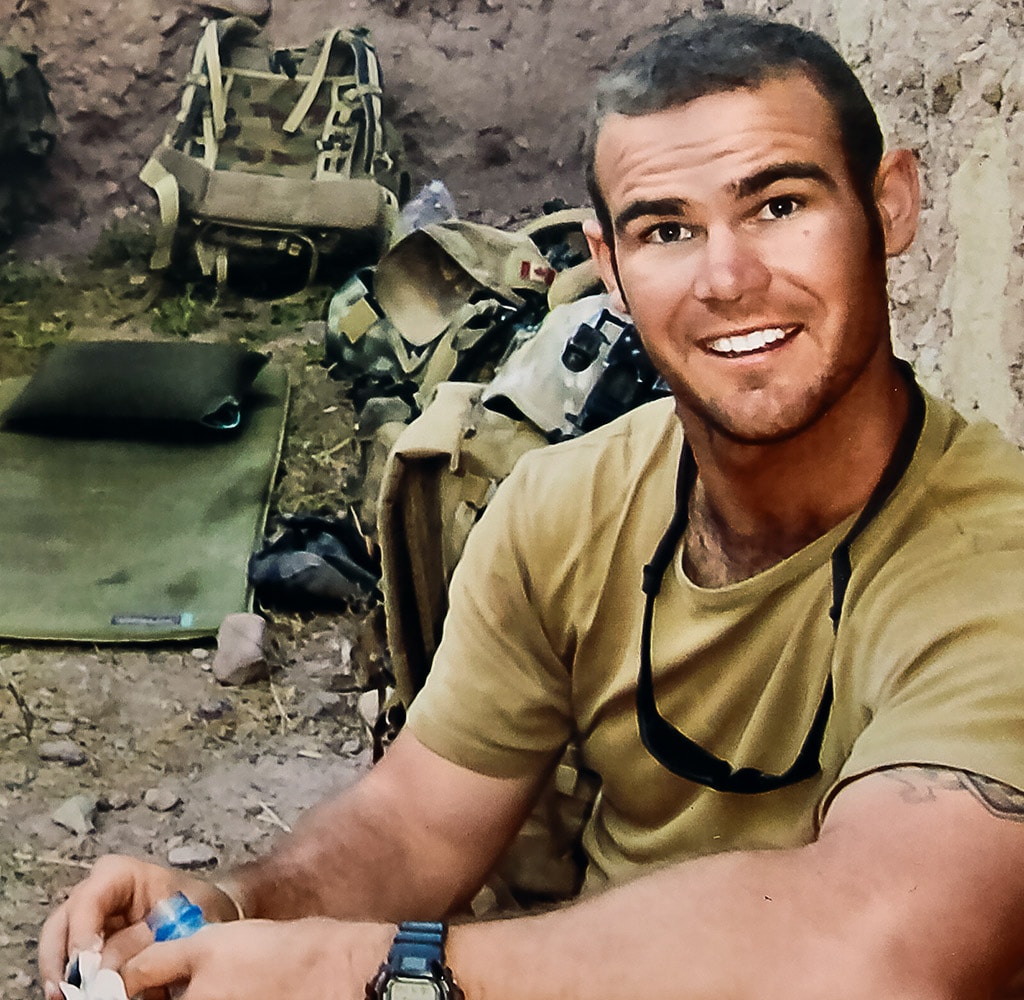

CAMERON BAIRD: 'I envisaged him as the next Wayne Carey' - Jude Bolton

As a young footballer and then as a career soldier, Cameron Baird was a self-sacrificing leader.

On the battlefield in Afghanistan in 2013, Baird made the ultimate sacrifice – and became

a hero of a nation.

It’s sobering to ponder that had he been drafted by an AFL club and forged a League career – as many wise heads thought he would – Baird probably wouldn’t have even joined the army, let alone been killed and awarded a VC posthumously.

Baird inherited his footy genes from his father Doug, a full-forward who graduated from Carlton’s under-19s and reserves to play six senior games as a teenager under Ron Barassi in 1969-70. The family remain Blues fans.

Doug Baird regrets that he didn’t play more League football, but he couldn’t resist the money on offer in the VFA and became a premiership star for Brunswick in 1975.

The next year he accepted another lucrative deal with Tasmanian club Cooee, near Burnie.

Cameron was born in Burnie on June 7, 1981, and was three when his family returned to Melbourne, settling in the northwest suburb of Gladstone Park.

Big for his age, Cameron led Gladstone Views Primary School to runner-up in the 1993 statewide competition and captained the championship-winning Victorian primary school team that boasted future AFL players Jonathan Brown, Leigh Brown, David Teague and Steven Greene.

Cameron Baird (circled) in the Victorian Primary Schools team of 1993

At junior level, Baird was also a national discus champion and a state shot put champ. But footy was his passion, and he dreamt of following in his father’s footsteps to Carlton.

An AFL career beckoned.

After starring for Gladstone Park and then Strathmore, Baird started playing for TAC Cup team Calder Cannons at the exceptionally young age of just 15.

Among his teammates were future AFL premiership players Paul Chapman, Jude Bolton and Ryan O’Keefe.

For the 2017 book The Commando: The Life & Death of Cameron Baird, VG, MG, Bolton told author Ben Mckelvey of Baird’s enormous potential: “I envisaged him as the next Wayne Carey. He was very Wayne Carey-like. He had that waddle and was very strong above his head … he was one of those guys you’d go into battle with. He was extremely courageous.”

In 1998, Baird won the Cannons’ goalkicking with 35 in 20 games.

He also loved the game so much that, according to Cannons teammate David Johnson (later a Geelong player), Baird once joked: “‘Johnno’, one day I will bring out a perfume called Sherrin. If a woman smelled like a Sherrin, I wouldn’t be able to keep my hands off her.”

Some AFL clubs had indicated they wanted to get their hands on Baird, who impressed in a 1999 reserves game for Geelong, kicking two of his team’s four goals.

Then he suffered an ill-timed shoulder injury that required surgery and sidelined him for the rest of the season. He still kicked 22 goals in nine games, but was overlooked in the 1999 National Draft.

“When he wasn’t drafted, he went for a walk,” Doug Baird told Madden. “I think there’s no doubt he shed a tear … (but) he quickly gathered himself and I think he saw there was a new challenge in life. That challenge was the Australian army.”

Baird soon suffered another setback when he was rejected by the army on medical grounds, courtesy of his shoulder problem.

However, the teenager lodged an appeal and the decision was overturned.

In January 2000, at a time he’d originally envisioned doing his first AFL pre-season, Baird started training to become a special forces soldier. He never played football again.

A month later, Private Baird was transferred to the 4th Battalion (Commando) – later renamed the 2nd Commando Regiment – and served in East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan (where he had five tours of duty).

He grew to be a big, strong, athletic man of 192cm and 90kg – an awe-inspiring sight in combat, yet he was also known as a gentle giant.

The fearless Lance Corporal Baird was awarded the Medal for Gallantry (MG) in Afghanistan in 2007.

While attacking a Taliban stronghold, one of Baird’s platoon members was mortally wounded. Under heavy fire, Baird recovered his fallen mate, before leading the way in clearing the enemy compound, killing several Taliban fighters and preventing further Australian casualties.

His MG citation noted that the 26-year-old had “displayed conspicuous gallantry, composure and superior leadership under fire”.

In earning his Victoria Cross more than five years later, Baird was even more conspicuous (indeed, author Madden marvelled at his “almost inhuman audacity and courage”), but not as lucky.

The citation for Corporal Baird’s VC recognised the 32-year-old “for the most conspicuous acts of valour, extreme devotion to duty and ultimate self-sacrifice”.

On June 22, 2013, Baird’s Commando team was part of an operation to attack insurgents deep in enemy territory in Ghawchak village, Uruzgan province.

Under his nerveless leadership, they “neutralised” several enemy positions, at times after Baird had charged straight at those posts. Corporal Baird stormed the door of an enemy compound three times, each time being “totally exposed” and coming under heavy fire from close quarters.

At first he was forced to withdraw because his rifle malfunctioned.

On his third attempt, when he deliberately drew fire away from his team, the enemy was defeated.

But when the smoke and dust cleared, Corporal Baird was dead.

He’d once told his mother Kaye: “It could happen to me, it could happen to anyone, any time. We know the dangers, but it’s our job.”

Doug Baird told Madden: “In that particular battle, I think that 28 Taliban insurgents were killed – and one Australian soldier” – the one Aussie being his son. “Could’ve been a lot worse,” he said.

In announcing Baird’s death, Australia’s Department of Defence stated: “He exemplified what it meant to be a Commando, living by the attributes of uncompromising spirit and honour … Corporal Baird died how he lived – at the front, giving it his all, without any indecision.”

Australia’s then-defence chief General David Hurley hailed Baird as “a true modern-day warrior”, while the army’s warrant officer Dave Ashley saluted “one of Australia’s greatest ever soldiers”.

In February 2014, Australia’s then-Governor-General Quentin Bryce presented the VC to Baird’s parents.

There have been other posthumous tributes.

In 2016, a life-sized statue of Baird was unveiled at Currumbin RSL in the Gold Coast region, where his parents have lived for some years and where Baird was laid to rest.

In 2013, the Calder Cannons also struck the Corporal Cameron Baird VC MG Award for the club’s most courageous player.

Baird might well have been embarrassed by it all. His older brother Brendan told Madden “you would never know that Cameron was a highly decorated special forces soldier” because while others were “busting” to ask him questions, he’d divert the conversation away from himself.

Doug Baird told the AFL Record: “The pain never goes away, but we’re better adjusted now than we were a few years ago.”

The family has channelled its pain into Cam’s Cause, a not-for-profit charity that celebrates his life and aims to “inspire the leaders of tomorrow”. There are also plans to help with soldier welfare.

THIS STORY APPEARS IN THE ROUND-FIVE EDITION OF THE AFL RECORD, AVAILABLE AT ALL VENUES.