DUNCAN Wright has only one regret. But it's not the one you might expect.

Many will say Wright should harbour greater remorse about the incident that hastened the end of his League career when he knocked out Essendon opponent John Somerville behind the play in the 1965 preliminary final.

But the infamous former Magpie has never been the regretful type. At 74, he remains a hard nut to crack.

"What's done is done," Wright says. "No point worrying about the past. Only worry about the present and the future."

As he ponders his turbulent 23-game career at Collingwood, the old-school hardman shows the first signs of emotion.

"If I had have been allowed to stay (at Collingwood), I would've played a lot more games. And I would've loved to have stayed there," Wright says, before staring off into the distance and taking a long pause.

Tears well in his eyes. His face reddens.

"Perhaps I should've toed the line more," he concedes.

But on the incident that changed his life forever, Wright remains unrepentant and cites provocation as the reasons for his actions.

Unfortunately we only have his side of the story, as Somerville died suddenly at just 44 in 1984.

We're seated in the old grandstand at Alphington Park, in Melbourne's inner north-east, where Wright's football career started as a junior and finished as a veteran.

Wright's childhood home and school are both within 200m. He has lived nearby virtually his whole life.

He has played at the adjacent bowls club for 14 years and every week someone notices his name-tag and asks, "You're not the Duncan Wright are you?" "Yeah, that's me," comes the well-worn, matter-of-fact reply.

Wright concedes he was extremely lucky to get a game in the 1965 preliminary final. He'd played just two games to that point, after suffering two serious injuries: several broken ribs and a punctured lung in round one, and a broken collarbone on his return 10 weeks later.

Wright describes his third game for the season as "an even worse disaster".

He started at half-back where he niggled the slightly smaller Graeme Johnston, who quickly swapped flanks with Somerville.

Wright and Somerville could scarcely have been more contrasting players and characters. Somerville, also 25, was tall and lean at 188cm and 79kg (8cm taller but 4kg lighter than Wright) and nicknamed 'Slim'.

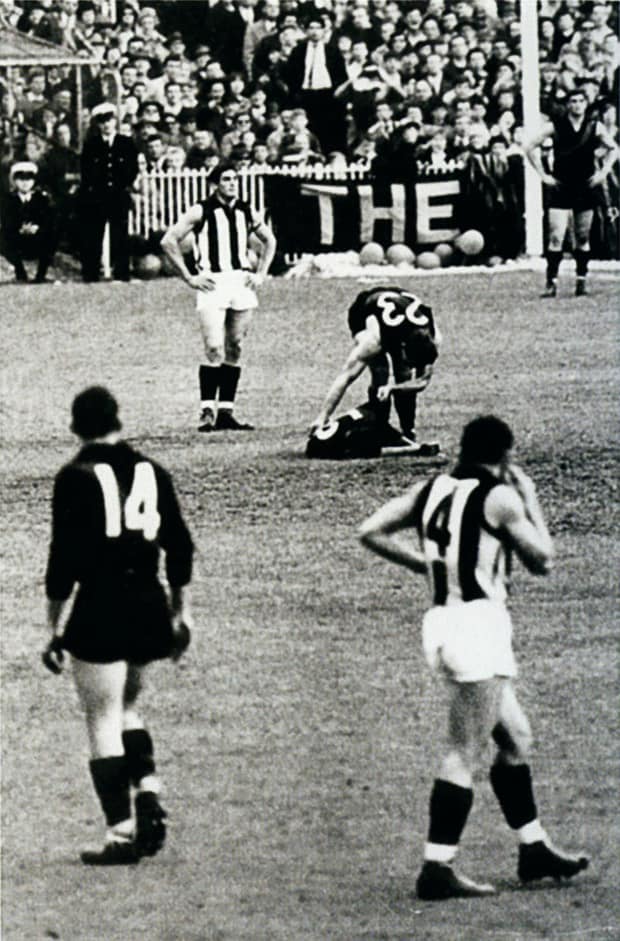

Out cold: Duncan Wright standing over John Somerville in the 1965 preliminary final. Picture: Courtesy of the Official Collingwood Illustrated Encyclopedia

A quiet, respectful country boy from Moe, in Gippsland, the 1962 premiership player was graceful, a very good kick and a ball player. Not noted for his physicality, Somerville was never reported in his 106 League games.

Nine minutes into the match, with the ball about 40m downfield, there was confusion and then pandemonium as spectators and players noticed Somerville lying motionless near a seemingly nonchalant Wright. The photograph of the incident has gone down in footy folklore.

None of their teammates saw the incident. Nor did the sole field umpire, Ron Brophy.

That Wright had hit Somerville is not in dispute, but the motivation remains debated.

Wright is adamant he was provoked, insisting Somerville "started mouthing off and niggling" before back-heeling his shins and then "squirrel-gripping". He says he warned Somerville three times to quit it or else, but Somerville "didn't take any notice".

"I wanted to put a stop to it, and I did. It mightn't have been too smart, but it's too late (to change it) now."

But others – including Somerville's teammates, his son Peter (the Bombers' 1993 premiership ruckman) and umpire Brophy – believe Somerville would have been the last person to intentionally rile a volatile type like Wright. Such tactics, they say, would have gone against Somerville's nature as a player and person.

Ken Fraser, Essendon captain at the time, admits players are capable of uncharacteristic behaviour in the heat of the moment, but says he never saw any aggression from Somerville.

In any case, Pies star Des Tuddenham says he saw them jostling beforehand, but didn't think it was anything out of the ordinary.

Peter Somerville was born almost three years after the incident, soon after his father's League retirement, and was only 16 when Somerville snr died. He says his father didn't like to talk about it and suspects this was because "it would've eaten away inside him" that it cost him the chance to be a dual premiership player. (Somerville spent two nights in hospital with severe concussion and missed the Grand Final.)

"The cruel joke was that the old man fainted before the first bounce, which was pretty embarrassing to hear from people," Peter Somerville said.

"Dad copped that and even I did. Years later a spectator told me he saw what happened. He said they'd had the usual argy-bargy and when the old man walked in front of Wright he just went bang."

Confronted with views that question his version, Wright asserts: "I don't care what people say. You don't hit somebody for no reason."

Duncan Wright at the Alphington Football Club. Picture: Michael Willson

Fraser was the first player on the scene, where Somerville was face down and unconscious. Wary of causing further injury, Fraser gently lifted Somerville's shoulder to aid his breathing. He also waved over the trainers and prompted Brophy to hold up the game.

The incident appeared to have dramatically opposite effects on the teams: Essendon's resolve was steeled, while Collingwood seemed rattled by the incessant booing of incensed Essendon fans.

Wright says he didn't notice the hooting – "All you hear is noise, and you don't know if they're with ya or agin' ya."

As Fraser told his teammates individually to "focus on football and only hurt Collingwood on the scoreboard", rugged vice-captain Ian 'Bluey' Shelton quietly ordered them to seek vengeance.

"Collectively as leaders we did the right thing," Fraser said. "The ball players played the ball and the more aggressive types had full licence too. We had everyone playing their natural game and we won well (by 55 points)."

Wright says he wasn't singled out for criticism or even stern questioning by anyone in the Magpie camp post-match. "They were all supportive of me," he says.

Typically, Wright says he didn't even have any concern for his safety when leaving the ground.

But Pies coach Rose ordered a handful of players to form a human shield around Wright to escort him to his car in the surrounding parkland. They copped only verbal abuse.

"I don't think Duncan needed any help," Tuddenham says.

Wright was eligible to play in the reserves Grand Final, and wanted to play, but the Pies decided it would be best if he attended a mate's wedding in Warrnambool instead. It was a convenient and probably wise way to avoid further unwanted attention – of which there was plenty.

Victoria Police chief commissioner Rupert Arnold assigned two homicide detectives to the case, and Wright was lucky to be represented by famous lawyer Frank Galbally, a staunch Collingwood figure.

Wright was interrogated for 90 minutes at Victoria Police headquarters in Russell St but, under instructions from Galbally, answered every question: "No comment." He recalls: "In the papers it said: 'Wright speaks' and then further down it said: 'No comment.'"

Various spectators came forward claiming to have witnessed the incident, but gave conflicting accounts. No charges were laid. The League also decided against further investigation.

However, the controversy took a large toll on Wright's family. His mother – whom he says was a gentle woman who had never wanted him to play football – received a letter threatening to bomb her house. He says the stress almost caused her to suffer a nervous breakdown.

"That upset me," Wright says.

Another casualty of the incident was umpire Brophy. After officiating in the previous year's Grand Final, Brophy was demoted to a country league grand final but retired on principle.

"(Brophy) got rubbed out because he didn't report me. But how can you report anybody if you didn't see the incident?" Wright says.

Wright had also featured in his last League game. He didn't see it coming either – after all, he'd joined the Pies on an end-of-season trip to Japan and had no inkling he had become persona non grata.

It wasn't until after he played the last of five practice games before the 1966 season that he was told he was no longer required. Publicly the Pies explained they had too many half-back flankers, but Wright suspects otherwise.

Tuddenham says it was a mistake, and that Wright might have proved the difference in the 1966 Grand Final against St Kilda.

Twenty years later, Wright went to a sportsmen's night and bumped into former coach Rose, who apologised for letting him go. It was cold comfort for Wright.

After his sacking, Wright went to Canberra to work and play football and get out of Victoria, but soon returned to play local footy.

The Somerville incident never followed him on the field. It was different in pubs, where he was "harassed" for 20-odd years.

The Sporting Globe took Wright to Somerville's farm at Moe for a story in 1982 (two years before Somerville's death). It was the first time they'd seen each other since what Wright calls "that fateful day".

Greg Hobbs, the journalist who orchestrated the meeting, said they exchanged phone numbers and vowed to get in touch.

Wright says: "We shook hands, and gave each other a kiss and a cuddle. Nothing more was said. There was no animosity."

In some ways it's difficult to reconcile Duncan Wright the footy villain with the loving, wise-cracking grandfather-of-five.

He becomes emotional again when he refers to them as his "best mates".

A grandson, Billy Hogan, who will be 20 next week, represented TAC Cup club Oakleigh Chargers and now plays for Port Melbourne in the VFL.

"He's a far better kick than his grandfather," Wright says. "He's a bit of a hothead too. Dunno where that comes from."